Claiming Settled Land: An Argentine Rebel War

Week 8 of the Quarantine

SAN MARTIN, ARGENTINA – “This is going to be tough,” said Elizabeth. “This is a real war.”

The war with the originarios has suddenly gotten hot.

Two of our houses were burned down. About a mile of our water line was pulled up and burnt. Roof beams… and the sepo – which locks the cattle in place while they are being vaccinated – were stolen.

Arson, larceny, vandalism. What will be next?

“They might burn down your house, too,” suggested Natalio, our oldest and most trusted ranch hand.

Above the Law

To bring new readers up to date, the originarios are a group of malcontents in Argentina (mostly in the mountains) who claim “indigenous rights” above and beyond the rights of others.

They say they are Native Americans – Indians – who have the right to the land they live on, with their own laws and customs.

There probably are real originarios somewhere who deserve special consideration so that they can continue to live in traditional ways on tribal lands.

But here in our area, there are no tribes and no tribal lands.

The tribes were conquered, dispersed, or killed in the 17th century. And the people now claiming tribal rights are no different – racially or culturally – from any of the other locals, including our own employees.

They drive pickup trucks, use iPhones, speak Spanish, and live off welfare payments. The ones on our property are not even from here. They were invited in by a previous owner to work on the farm. Now, they claim they own it!

“They were cattle rustlers from the Puna (the high desert on the other side of the cordillera, or mountain range),” says Natalio…

War in the Mountains

For the last few years, we’ve tried a policy of détente. That is, we left them alone. We asked them to sign their leases and pay their rents (largely symbolic).

They refused. And then, every time they broke down our gates, or caused trouble, we called the police.

But the courts are reluctant to get involved. Originarios are a protected species. And nobody knows who’s an originario and who’s not. The law says you can decide for yourself.

There was nothing more we could do. So, we figured we would wait them out.

It’s a rough life up in the mountains. The younger ones leave for the city and don’t come back. Besides, it was not worth fighting over.

One of our neighbors made peace with them. The terms are not yet public, but apparently he gave them the mountainous part of his property – some 100,000 acres – and each side agreed to respect each other’s interests.

But that neighbor is a grape producer. The mountains and high valleys are worthless to him. Here, we raise cattle. And we share our high pastures with our own ranch hands, their extended families, and others who just keep their cattle there.

They pay us by giving us a few scrawny cows each year. In exchange, they have the use of the pasture, and we maintain the corral, the houses that were just burned down, and the sepo that is indispensable to all of them.

“They didn’t just declare war on you,” says Natalio. “They declared war on us, too. And the funny thing is they call us cholos too…”

A cholo is a “half-breed.” Natalio, of course, is more originario than the originarios. He’s spent his whole life here… His family has always been here. But now the originarios brand everyone who cooperates with us as a cholo.

Riding Out at First Light

On Saturday, we rode up to have a look for ourselves. At first light, we mounted up. Natalio accompanied us.

We rode our horses. Natalio was mounted on one of our mules, trailed by two small dogs. The mules are better for the mountain tracks, where we were going.

The temperature was below freezing. We had dressed lightly, counting on the sun to warm us. But for the first two hours, the sun was blocked by the mountains on the east side of the valley.

The trail wound around the mountainsides, following the course of the river below. Then, it rose over a hill… and kept rising until finally we felt the sun on our backs.

From there, it was up and up… and up some more. Each time we thought we had reached the crest of the pass, we found another one ahead… higher still.

Finally, after about three hours, we were at about 12,000 feet and looking down on the broad valley in the distance.

Legend of the Originarios

The originarios live in two big valleys. Both are part of our ranch. But the originarios claim them as part of their tribal land. The only trouble is, they have no tribe.

They say they are Diaguita, but local historians say the Diaguita never lived in this area and haven’t existed for at least 300 years.

Instead, they say the “Diaguita” tribe was reinvented by an opportunist, whose mother was German and who now lives in London. Asked about the tribal connection, his father told a local newspaper that it was all just made up.

The big valley is probably about 10,000 acres, with a river flowing through it. In the dry season, the river goes underground and the grass dies.

We used to keep about 200 cows up there. They competed with sheep, burros, and llama for the grass. But three years ago, a drought forced us to bring the cattle down.

Then, when we tried to put them back, the originarios blocked the road.

Our cowhands didn’t want that kind of trouble. So, we backed off. It wasn’t worth a fight. And in any tussle with the landowner, the originarios always win.

They are many; we are few. And they have the backing of the politicians.

Remote Inca Path

From the top of the pass, it takes about another hour to get down to the valley floor… and then yet another hour, along level ground, to where we have our corral.

The inaccessibility of the place is part of the reason the damage is so great. It is very difficult and expensive to get anything up there.

There are no trees. Every piece of wood must be carried up. Moving up roof beams is a major engineering feat. A burro, or donkey, can carry only one bag of cement.

We took a tractor and a small trailer up when we put in the water line, about five years ago. But it took nearly a week, repairing the road as we went… and losing about half the workday each day just getting to the jobsite.

The Valley of Compuel

The road follows an ancient Inca path. When it comes down from the pass it takes you to some ancient ruins.

There are acres of squared-off stone buildings. Archeologists don’t understand exactly what they were used for.

Near them is our corral, an impressive stone structure about half the size of a football field.

There, the cattle from the valley and all the surrounding mountains were herded together each year, to be branded, castrated, tagged, and vaccinated.

Assessing the Damage

By the time we got there and surveyed the damage, it was 2 p.m. Like cattle bones, picked over by the condor and bleached by the sun, there was not much left of our cabin.

The cattle chute was partially destroyed; the sepo was missing.

The cabin burned, the manga destroyed, the sepo stolen

Refuge in the Rocks

The wind was picking up. We took refuge up in the rocks to eat lunch.

It was a natural cave, formed by an overhanging rock. At the entrance, someone had made a rough stone wall.

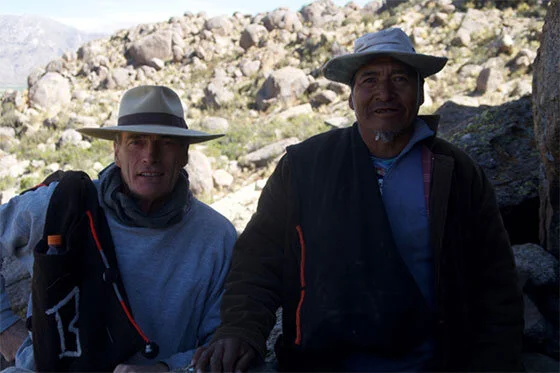

Bill and Natalio

Natalio spoke:

“Up in the mountains, you’ve got to round up the cattle on foot. And you look for a place like this to sleep. This is where I curl up when we do the roundup.

“One time, I was getting into a little place like this to get out of the wind when I heard a puma [mountain lion] growling. We see them skulking around high in the mountains, but we rarely get very close.

“They kill a lot of the calves. A lion will attack even a 2-year cow. It jumps on its back and rips its throat with its claws.

“Between the condor and the lions, we’re lucky if half the mountain calves survive.

“But one time I was looking for a place to get out of the wind. There was a nice little nook I was headed for when I heard the lion growl. I looked up. And it was almost right on top of me.

“We say lions are cowards. They almost never attack humans. But this one was coming right at me.

“I had a saddle blanket. I held it up to protect myself. I backed away… and yelled at the lion. It just stood there growling on top of the rock.

“And then I realized what had happened. There were two lion cubs in that cave. I got out of there as fast as I could.”

Natalio then turned to the subject at hand.

“We need that sepo. The round-up is in a few weeks. Without a sepo, it’s almost impossible to vaccinate cows.

“And we know where it is. Those [Natalio named the family that he thinks stole the sepo] must have it. They’ve always been a problem. My brother says they stole his calves.

“If this were the old days, we would ride out, find our sepo, take it back, beat them up, and burn down their houses, too.

“But those days are gone. Now, they get away with anything and we have to respect the law.”

Long Ride Home

We had seen the damage. We took our photos. It was time for the long ride home.

Natalio and dog; Cachi in the background

When we got back to the sala (the main farmhouse) we sent the photos to the police chief and asked him to send up someone.

The police are supposed to arrive on Friday morning.

In the meantime, our cowboys are out looking for the missing sepo. You can’t move that much stuff – beams, doors, and the sepo itself (made of heavy algarrobo wood) – without leaving a trail.

With luck, the trail will lead us right to the arsonists’ door.

We didn’t want a fight with the originarios. But we got one anyway.

Stay tuned…

Regards,

Bill